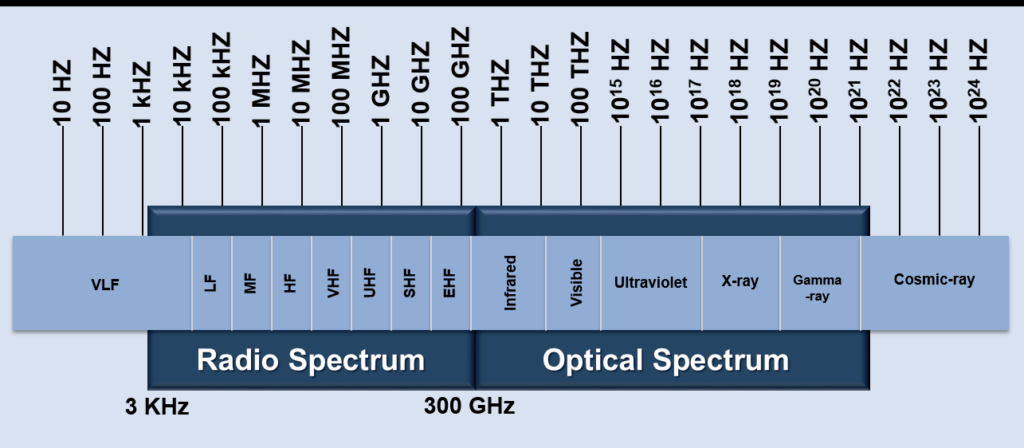

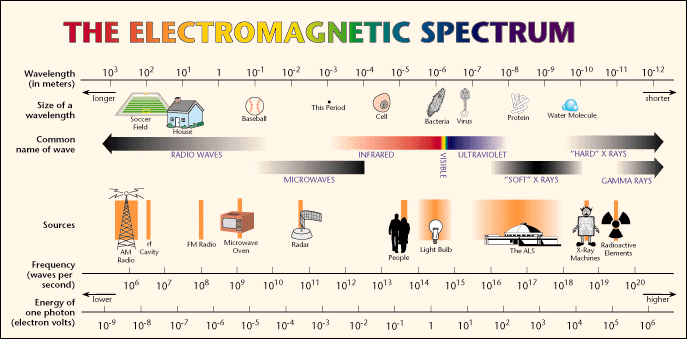

Frequency bands within the electromagnetic spectrum have multiple, sometimes confusing, overlapping designations.

Electronics engineers must deal with the electromagnetic spectrum as a routine part of their wired and wireless projects. This spectrum of interest ranges from relatively low frequencies in the kilohertz (kHz) range (or perhaps lower) into the tens and even hundreds of gigahertz (GHz), all the way to terahertz (THz) in some cases—and even extends into the optical and ultraviolet regions.

Being clear and unambiguous about where you are operating in that spectrum is an important first step in any design, as each region has its own attributes with respect to wavelength, absorption, range, penetration, applications, and more. However, all are ultimately governed by Maxwell’s equations (actually presented in the form we know them now by Oliver Heaviside, but that’s another story).

There are countless graphical representations of the electromagnetic spectrum ranging from straightforward, general high-level versions (Figure 1), to ones that attempt to make it clear to the general public (Figure 2).

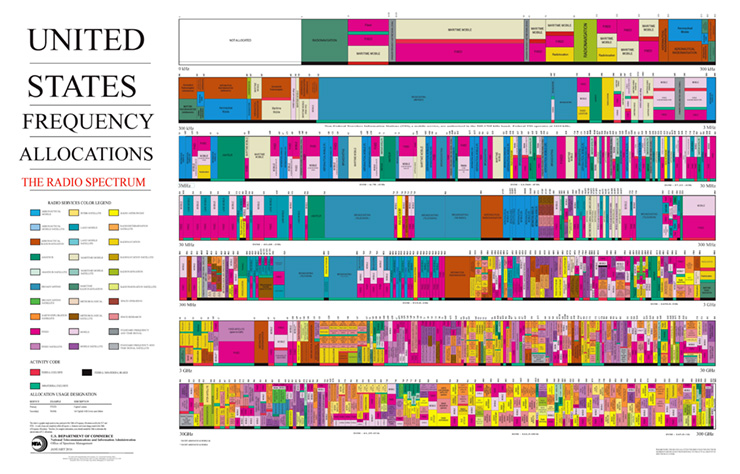

There are also highly detailed spectrum-allocation charts showing how the spectrum’s parts are divided and assigned by regulatory agencies for different users and applications (Figure 3). Large wall-size versions are available online to print out locally or can be ordered printed and ready to frame.

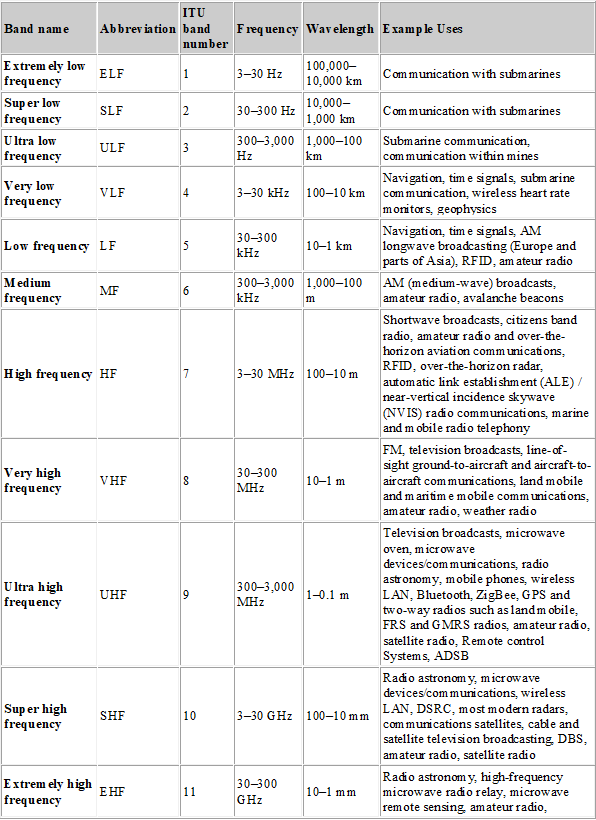

So how do you define where you are? There are several ways, some of which are unambiguous and some which can lead to confusion. Start with the more logical approach: the frequency band division by order of magnitude. The International Telecommunications Union (ITU), based in Geneva, Switzerland, has defined bands with both simple band numbers and a two/three-letter description (Figure 4).

[Note: Not shown here are band 0 (0.3 to 3 Hz) and even band -1 (0.3 to 3 Hz]

Mathematically, a band number “N” represents a span from 0.3’ 10N hertz (Hz) to 3’ 10N Hz, where 1 Hz is one cycle per second. (You will see the abbreviation “cps” units on older documentation, as the use of hertz to replace “cycles per second” was not officially established until 1960.)

The two- and three-letter descriptors were used more extensively in some applications and less in others. For example, the analog TV with 13 channels that were in use for 50+ years was broadcast initially in two segments of the VHF band; eventually, many more channels were added but in several segments of the UHF band. TVs were promoted as being VHF/UHF compatible to the general public and even needed a separate over-the-air (OTA) antenna for compatibility with the very different frequencies and parts of the spectrum. On the other hand, engineers working in the lower-gigahertz part of the spectrum rarely characterize it by the ITU designation of SHF.

What about letters?

So far, this is all fairly clear and unambiguous. However, the various bands within the spectrum also have letter designations due to historical precedents as well as informal industry nomenclature, which has become standardized to some extent. For example, you may see a component characterized as an “L-band” amplifier or an S-band mixer.

What does this mean? There are several overlapping and even contradictory naming systems for microwave bands, and even within a given system, the exact frequency range designated by a letter may vary somewhat between different application areas.

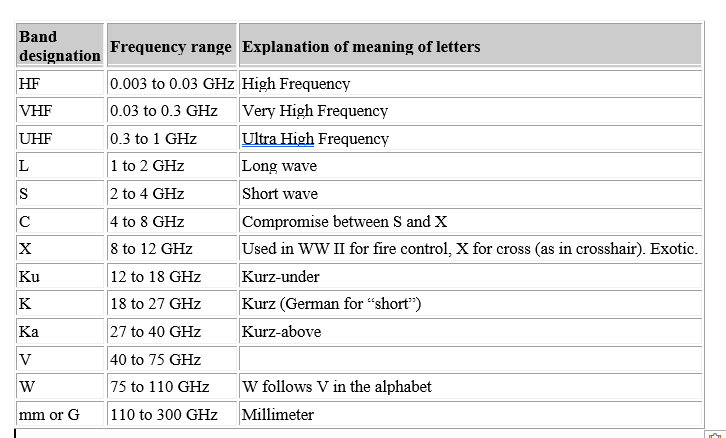

The use of letters for bands began around World War II with military designations for frequencies used in radar, which was the first application of microwaves. (Incidentally, there is no formal definition of “microwaves”, but the general usage is that they represent frequencies from 300 MHz to 300 GHz, corresponding to wavelengths from 30 cm down to 1 mm.) Due to wartime military secrecy, the exact frequency band corresponding to each letter was classified, leading to rough “guesses” for the band corresponding to each letter and some confusion.

In 1976, the IEEE began a process of standardizing letter designations. IEEE Standard IEEE 521, “Letter Designations for Radar-Frequency Bands”, was updated in 2002 (Figure 5); a point of potential confusion is that the standard is not just for radar applications, despite its name.

Note that some older tables show the border between K and Ka designations to be 26.5 GHz, not 27 GHz. Also note the historical connection of some designations such as Ku, K, and Ka, which otherwise seem to have no logic to justify them.

But wait… there’s more

Over the decades of spectrum use and extension to higher frequencies, several informal or proprietary letter designations and bands have been used. In other cases, the broader official letter designations have been subdivided by engineers focused on applications in a relatively narrow bandwidth within the broader band. Figure 6 shows one consensus of these alternatives and additional designations.

Note that, again, some of the frequency boundaries have shifted slightly, in addition to subdivided.

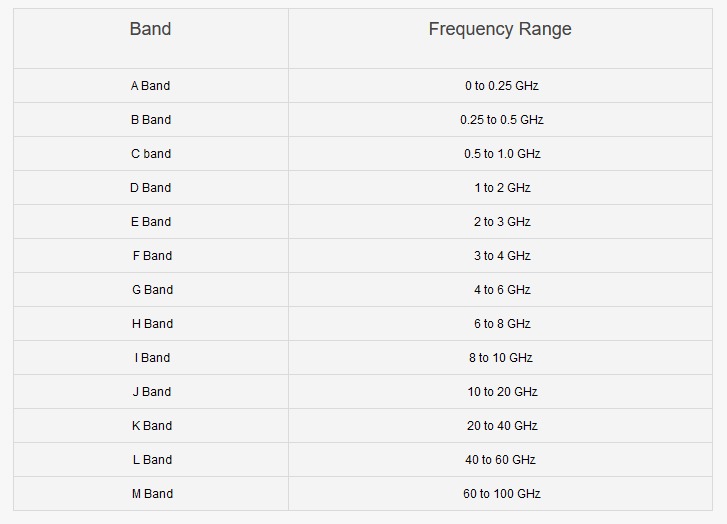

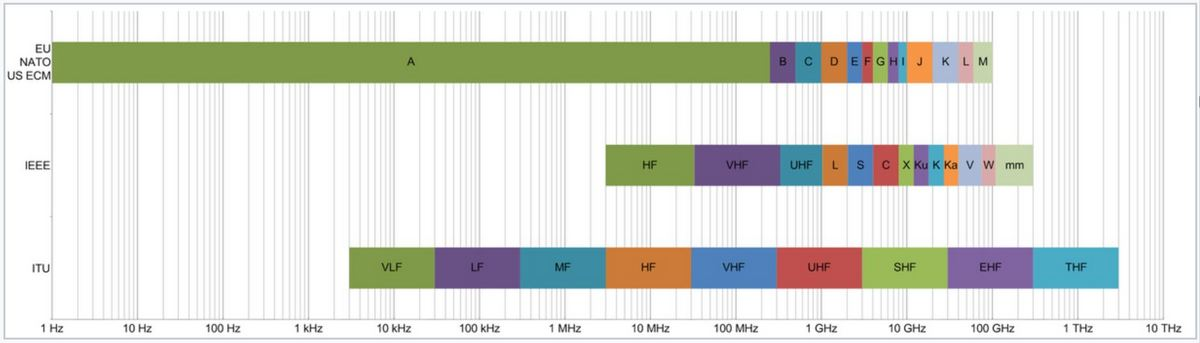

Does the story of letters and band designations end here? No, it does not. NATO, the European Union, and US military radar specialists used a different set of letter designations primarily for radar and electronic countermeasure (ECM) applications before standardization by the ITU and IEEE. They started with an “A” band and proceeded in alphabetical order to M (Figure 7), and these designations linger in the literature:

Since this NATO/EU/US ECM listing is focused on radar and ECM applications rather than more-general wireless uses, it has a very wide band slice “A” all the way to 250 MHz (0.25 GHz) and then a much-narrower progression of spectrum slices above that frequency.

It’s helpful to look at the multiple band-designation schemes in a single overlay (Figure 8). Note that the EU/NATO/US ECM “L” band is very different than the IEEE “L” band; similarly, the “G” band in IEEE terminology is orders of magnitude different than it is in the others.

The bottom line

When you’re working in these RF bands, be sure to confirm the specific frequency of interest in hertz (MHz, GHz, THz) in addition to using the letter designation. The reason is that one person’s letter band may differ from another person’s, especially in their boundaries. Also, the bands are pretty wide, so simply saying it’s an amplifier for the “such-and-such” band could refer to the entire band or perhaps just to a sliver within the band. For example, I have seen promotional literature and datasheets for an “X-band amplifier” (nominally 8 to 12 GHz), which only has detailed, full specifications for 8 to 10 GHz, although it will work to some unspecified extent through the rest of that band.

In short: prudence and good engineering practice is always to verify and confirm that all of your referring same band and numerical part of the spectrum is in Hz.

Related EE World Content

What are the telegrapher’s equations?

Terahertz research: The road to 6G with Northeastern University

Lasers, optics, electronics, and more yield terahertz sources, Part 4 – Laughing gas

Demonstrating continuous terahertz sources at room temperature

Can Wi-Fi 6E really share the spectrum with incumbents?

Five key considerations for spectrum analyzers

Optical links for spacecraft, Part 1: The throughput limitation

Gain blocks extend the performance of space-qualified InGaP amplifier technology to the X-band

12 GHz: Claims and counterclaims take hold

Magnetron, Part 2: History and future

External References

- ITU, Recommendation ITU-R V.431-8 (08/2015), “Nomenclature of the frequency and

wavelength bands used in telecommunications” - TeraSense, “Radio Frequency Bands”

- AWT Global, “EU, NATO, US ECM Frequency Designations”

- Knowino, “EU-NATO-US frequency bands”

- Knowino, “ITU frequency bands”

- Knowino, “IEEE frequency bands”

- RF Wireless World, “TV channel frequencies”

- Everything RF, “Microwave Frequency Bands”

- Microwaves 101, “Frequency Letter Bands”

- General Services Administration, “Electronics for G-band ARrays (ELGAR)”

- Military & Aerospace Electronics, “Smiths Interconnect receives contract…to develop an integrated G-Band Satellite Based Antenna system…”

- Military & Aerospace Electronics, “DARPA asks industry to develop G-band RF and microwave enabling technologies for communications and sensing”