Fusion power has the potential to provide clean and safe energy that is free from carbon dioxide emissions. However, imitating the solar energy process is a difficult task to achieve. Two young plasma physicists at Chalmers University of Technology have now taken us one step closer to a functional fusion reactor. Their model could lead to better methods for decelerating the runaway electrons, which could destroy a future reactor without warning.

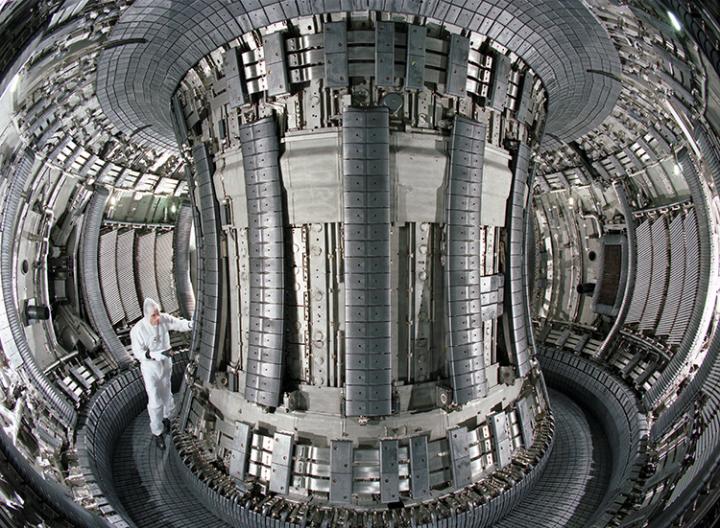

It takes high pressure and temperatures of about 150 million degrees to get atoms to combine. As if that was not enough, runaway electrons are wreaking havoc in the fusion reactors that are currently being developed. In the promising reactor type tokamak, unwanted electric fields could jeopardise the entire process. Electrons with extremely high energy can suddenly accelerate to speeds so high that they destroy the reactor wall.

It is these runaway electrons that doctoral students Linnea Hesslow and Ola Embréus have successfully identified and decelerated. Together with their advisor, Professor Tünde Fülöp at the Chalmers Department of Physics, they have been able to show that it is possible to effectively decelerate runaway electrons by injecting so-called heavy ions in the form of gas or pellets. For example, neon or argon can be used as “brakes”.

When the electrons collide with the high charge in the nuclei of the ions, they encounter resistance and lose speed. The many collisions make the speed controllable and enable the fusion process to continue. Using mathematical descriptions and plasma simulations, it is possible to predict the electrons’ energy – and how it changes under different conditions.

“When we can effectively decelerate runaway electrons, we are one step closer to a functional fusion reactor. Considering there are so few options for solving the world’s growing energy needs in a sustainable way, fusion energy is incredibly exciting since it takes its fuel from ordinary seawater,” says Linnea Hesslow.

She and her colleagues recently had their article published in the reputed journal Physical Review Letters. The results have also attracted a great deal of attention in the field of research. In a short period of time, 24-year-old Linnea Hesslow and 25-year-old Ola Embréus have given lectures at a number of international conferences, including the prestigious and long-standing Sherwood Fusion Theory Conference in Annapolis, Maryland, USA, where they were the only presenters from Europe.

“The interest in this work is enormous. The knowledge is needed for future, large-scale experiments and provides hope when it comes to solving difficult problems. We expect the work to make a big impact going forward,” says Professor Tünde Fülöp.

Despite the great progress made in fusion energy research over the past fifty years, there is still no commercial fusion power plant in existence. Right now, all eyes are on the international research collaboration related to the ITER reactor in southern France.

“Many believe it will work, but it’s easier to travel to Mars than it is to achieve fusion. You could say that we are trying to harvest stars here on earth, and that can take time. It takes incredibly high temperatures, hotter than the center of the sun, for us to successfully achieve fusion here on earth. That’s why I hope research is given the resources needed to solve the energy issue in time,” says Linnea Hesslow.

Facts: Fusion energy and runaway electrons

Fusion energy occurs when light atomic nuclei are combined using high pressure and extremely high temperatures of about 150 million degrees Celsius. The energy is created the same way as in the sun, and the process can also be called hydrogen power. Fusion power is a much safer alternative than nuclear power, which is based on the splitting (fission) of heavy atoms. If something goes wrong in a fusion reactor, the entire process stops and it grows cold. Unlike with a nuclear accident, there is no risk of the surrounding environment being affected.

The fuel in a fusion reactor weighs no more than a stamp, and the raw materials come from ordinary seawater.

As yet, fusion reactors have not been able to produce more energy than they are supplied. There is also a problem with so-called runaway electrons. The most common method of preventing this damage is to inject heavy ions, such as argon or neon, which act like brakes due to their large charge. A new model developed by researchers at Chalmers describes how much the electrons are decelerated, paving the way to making these runaway electrons harmless.