The electronically controlled, cam-free internal combustion engine seemed like a good idea, but technical and market realities stifled its acceptance.

Despite all the attention given to electric vehicles (EVs) as the inevitable replacement for vehicles powered by the venerable internal combustion engine (ICE), the reality is that for the foreseeable future, cars and trucks will use the highly refined ICE approach. Fewer than 5 percent of the cars sold in the US last years were pure EVs, and that number is expected to rise to perhaps 10 or 20 percent over the next decade. Of course, the actual number could be much higher or stay about where it is, despite the confidence of pundits and market-forecast organizations. Any accurate predictions of this type are hard to make, as the number depends on so many unknowable technical, regulatory, and user-perception factors and fears. In all likelihood, ICE-based vehicles will still “rule” the road for the foreseeable future, despite the many optimistic predictions, hopes, and investments.

The fact is that whether you drive a basic older car or a fancy, top-of-the-line model, as long as your vehicle has an internal combustion engine, it has cams that drive engine valves and control their timing. Under the control of cams connected to the engine crankshaft, the valves allow the ignitable gas-plus-air mixture into the cylinders and the exhaust out of the cylinders at precise moments. This timing is critical to the four-stroke combustion process standard in automobile and truck gasoline and diesel engines.

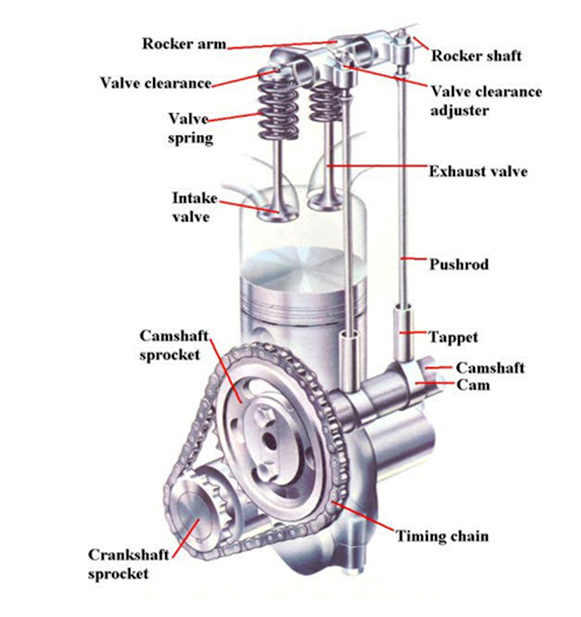

The standard crankshaft, cam, and valve combination, referred to as the valve train, is a whirring, interlocked set of mechanical pieces that use either pushrods and springs or an overhead cam and direct engagement to control the valve motion via rocker arms. The cam-based system is complex but reliable due to years of refinement over billions of units in long-term operation in the field. Although the cam-based system is relatively inflexible, it is especially reliable when flexibility in operation and timing are not a priority. In addition, it is entirely composed of visible mechanical parts with no computer-based firmware (with a few exceptions, called out below)

Cams set the pace for valves

The traditional pushrod-based valve train begins at the engine’s crankshaft, which converts the up-and-down motion of the pistons in the cylinders into rotary motion (Figure 1). In addition to conveying engine power to the transmission, the crankshaft drives a camshaft through gears or a chain.

The rotating camshaft’s lobes push on vertical metal rods (pushrods), which serve two purposes: They carry the camshaft motion from the bottom of the engine where the camshaft is located to the top of the engine where the cylinder’s valves are located. They also convert the lobe’s rotation into up-and-down motion. Then, the pushrods move rocker arms.

As a pushrod raises one end of a rocker arm, the other end moves down, which opens the valve associated with that rocker; as the pushrod moves down, the valve end of the rocker arm rises and closes the valve. The shape of the cam is extremely critical. It not only opens/closes the valve but it must be designed to not “slam” the valve closed too rapidly (which would cause undesired wear on the engine and audible noise) or too slowly (which degrades engine performance and efficiency), among other requirements.

The next part of this article examines some of the limitations of these cam-based systems, along with some enhancements that have been used to improve them.

Related EE World Content

Understanding stop/start automobile-engine design, Part 6: Responses and work-arounds (has links to previous Parts 1 through 5)

Digital Valves Open Up New Possibilities For Engines

Single element, tooth-detecting speed sensor IC

References

- Car and Driver, “Variable Valve Timing Explained: An Appreciation of How Quickly Engines Operate”

- New Atlas, “World’s first fully digital valves open up engine possibilities”

- Motor Authority, “Fully digital valves could change the future of the combustion engine”

- Motor Authority, “ ‘Engineering Explained’ tackles Koenigseggs camless engine”

- Clemson University, “Electronic Valve Timing Control”

- Clemson University, “Camless Engines”

- Motor1, “Fully Digital Valves Could Massively Improve The ICE”

- Wikipedia, “Camless Piston Engine”

- Top Gear, “Here’s how the Koenigsegg Gemera’s 600bhp camless engine works”

- Hackaday, “Where Are All The Camless Engines?”

- The Wall Street Journal, “Gas Engines, and the People Behind Them, Are Cast Aside for Electric Vehicles”

- Wikipedia, “Desmodromic valve”

- Virtual Energy, “Camless Hydraulic Valve Actuation (HVA)”

- Machine Design, “Improving Car Engines with Advanced Variable Hydraulic Valves”

- Skill-Lync, “Design and MBD Simulation of IC Engine Valve Train and FEA Analysis of Rocker Arm”

- University of Waterloo, “New Fully Flexible Variable Valve Actuation System”

- University of Waterloo, “New Fully Flexible Variable Valve Actuation System”

- University of Waterloo, “Hydraulic Variable Valve Actuation System: Development & Validation”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.