A critical constraint for edge devices is power availability—as the name implies, an edge device can exist or move among any number of far-flung locations where a power supply is not available. Consider, for example, a tracker application in which a device is dropped into a parcel consigned for shipment; the user can track the parcel during its journey and check its progress or condition. Clearly, no wired connections are possible, so the device must communicate wirelessly while relying on an internal power source.

In other scenarios, edge devices may be located in remote areas, and possibly in large quantities. Not only is mains power not available, but maintenance visits to replace batteries are also time-consuming and expensive. Edge sensor designers can respond by using rechargeable batteries or supercapacitors together with an energy harvesting strategy to recharge them in the field. Energy harvesting is attractive, as it taps into an inexhaustible supply of ambient energy. It is also challenging, and may not meet power needs of the node without a deliberate approach to low-power design.

Low-Power Design to Make Energy Harvesting Practical

Edge sensor power consumption is driven by the need to digitize, package, and transmit measured data to a gateway. These functions require at least the sensor, a microprocessor complete with crystal oscillator, memory array, and possibly A/D converter, plus the communications interface hardware.

There are a number of design techniques to minimizing power demand in an edge sensor:

- Sleep mode: choose a processor that can be efficiently driven into sleep mode when measurements aren’t necessary, and draws minimal leakage current while asleep.

- The choice of local network protocol: some protocols may have more data bandwidth than required, while drawing excessive power to communicate.

- Component choice and programming: overall, a designer needs to select a processor, memory subsystem, oscillator, and A/D converter for minimum power consumption, as well as coding the system to maximize energy efficiency.

By minimizing edge sensor power requirements, energy harvesting solutions may be sufficient to deliver the power required when ambient energy is available in adequate quantities. There are four main ambient energy sources available in the environment: mechanical, thermal, radiant, and biochemical. These energy sources are characterized by different power densities, the most popular being radiant and mechanical.

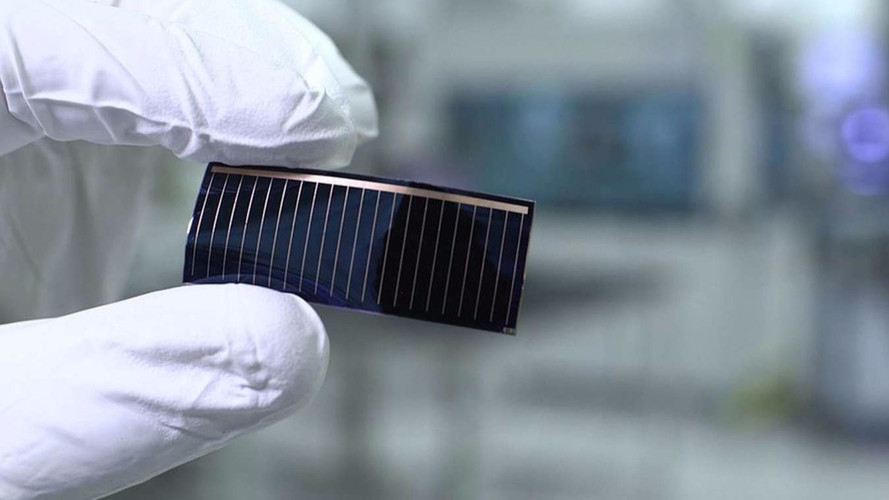

Capturing Radiant Energy with Solar PV Cells

Solar cells can harvest radiant light energy, converting it directly into a flow of electrons due to a photovoltaic (PV) effect. Solar cell technologies have evolved over three generations:

- First generation types are mainly based on silicon wafers and typically perform at about 15–20 percent efficiency. They offer good performance, but are rigid, and their production is energy-intensive.

- Second generation cells are based on amorphous (non-crystalline) silicon, so they cost less than first generation. They deliver typically 10–15 percent efficiency, and have some flexibility. Production is still energy intensive, and the use of scarce elements limits price reductions.

- Third generation solar cells use organic materials such as small molecules or polymers. Therefore, they offer great potential for advantageous pricing, efficiency, and are now being commercialized. Today, their performance and stability is currently limited compared to first- and second-generation products.

Solar energy has the potential to power IoT devices indefinitely, but there are application challenges. Many solar cells are too bulky, rigid, or inefficient for use in small and remote IoT devices.

Compact solar panels can also be used in applications that are extremely environmentally demanding: e.g., a solar-powered CattleWatch ‘smart collar’, which is exposed to mechanical stress and moisture. Placed in a herd of cattle, these smart collars form a wireless mesh network to share information. Ranchers can remotely manage the herd through satellite connectivity to the collars. Combined with industrial grade TLI Series rechargeable lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries, the solar panels help make the ‘smart collars’ lighter, more compact, and thus more comfortable for cows to wear.

Solar cells, packaged in panels, can scale up to power larger IoT devices as well. Wireless parking meter are highly power-efficient, harvest energy through a miniaturized PV solar panel, and store it in industrial grade TLI Series rechargeable Li-ion batteries. These autonomous meters connect to the Industrial IoT (IIoT) through a wireless network that permits more reliable efficient billing and reporting. They also reduce pollution by alerting nearby motorists when a parking space becomes available.

Harvesting Mechanical Energy in Everyday Activities

Kinetic energy from everyday activities can potentially be used to power smart devices. University of Wisconsin-Madison engineering researchers Tom Krupenkin and J. Ashley Taylor have developed an in-shoe system that harvests the energy generated by walking; they claim the system can generate up to 20 W of energy and stored it in an incorporated rechargeable battery.

The technology is based on a proprietary process known as ‘reverse electrowetting,’ which converts mechanical energy to electricity via a microfluidic device. Thousands of moving microdroplets interact with ” nanostructured substrate” to generate electricity. The process acts with various mechanical forces, which can output a wide range of currents and voltages. Investigators are looking onto ways for linking the battery to the phone using conductive textiles and wireless inductive coupling.

Very low levels of kinetic energy can also be used to power building automation and control systems. For example, EnOcean’s pushbutton modules incorporate rocker switches that operate on an actuating force of 7 N over a travel of 1.8 mm. Up to four pushbuttons can be accommodated within a single wall-mounting module. An energy converter, which works like a dynamo, converts the switch action into electrical energy with an output power of 120 µW. The module generates a radio signal when each pushbutton is either pressed or released. This contains a button code and unique module ID that a gateway can gather for a building automation system.

These pushbutton modules are complete edge sensor devices that manage the signal all the way through, from the switch to a reliable energy saving radio protocol. This not only ensures the low level of kinetic energy is successfully harvested for the application, but also that the product is easy for system developers to integrate into their building automation, home automation, or other projects.

Harvesting RF Energy through an Antenna

Radio frequency (RF) energy can be used to trickle charge or operate consumer electronics such as e-book readers or headsets, wearable medical sensors, and other devices. This power source is nearly ubiquitous because of the large and growing number of radio transmitters around the world, for TV and radio broadcasting as well as mobile phones and other devices.

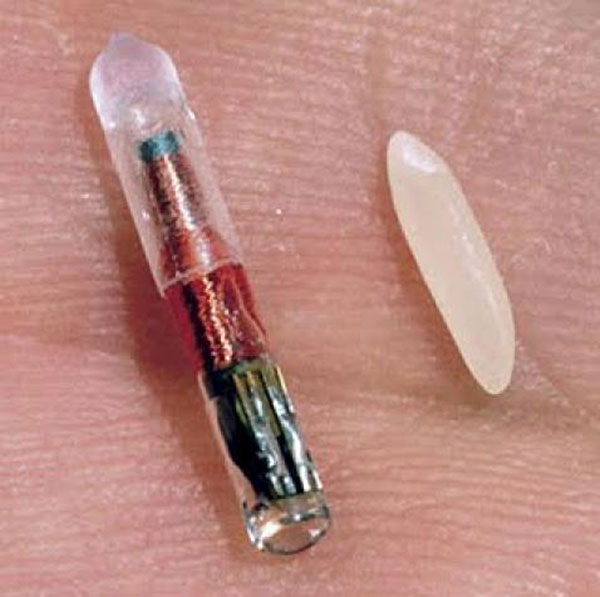

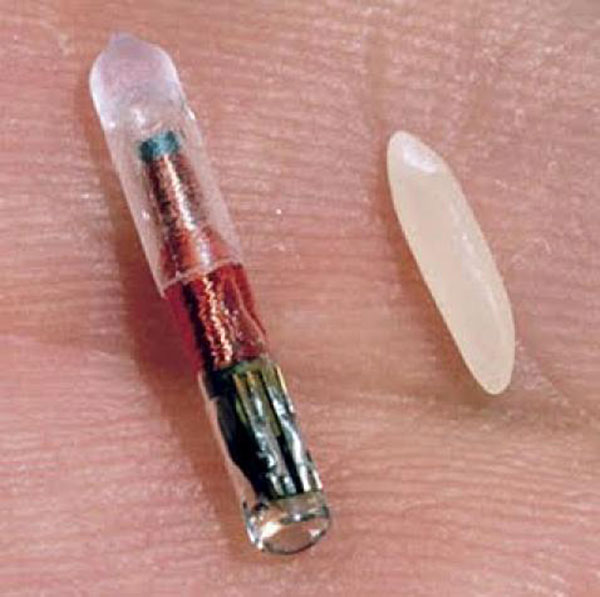

Radio-frequency identification (RFID) uses a special form of RF energy harvesting, in which power and information is obtained from a specific source, rather than random ambient RF energy. An RFID base station uses a scanning antenna to transmit RF signals over a relatively short range. The signal communicates with a transponder built into a passive RFID tag, providing the transponder with the energy necessary to wake up, read, and communicate in response. There are also active RFID tags with batteries that operate at a greater distance, but passive tags without batteries have a virtually unlimited lifespan.

Applications are widely diverse: examples include credit cards, real-time location systems (RTLSs) to track worker movements or the effectiveness of a store floor plan, asset tracking, motorway tolls, and pet ID implants.

Harvesting the Vibrational Energy of the Wind

Some techniques allow wind energy to be converted into vibration energy for harvesting. This has been demonstrated by a research project conducted at Chongqing University, China, to build a wind-powered temperature sensor node. The complete device measured 62 x 19.6 x 10 mm and comprised of a temperature sensor, piezoelectric wind energy harvester, microcontroller, power management circuit, and radio transmitter module. The critical wind speed proved to be about 5.4 m/s. If this increased to 11.2 m/s, the device provided 1.59 W into a 20 kΩ electrical load. This was sufficient power for the wireless sensor node to measure and transmit the temperature every 13 sec.

Storing Energy with Supercapacitors and Batteries

In many harvesting applications, the ambient energy source may be insufficient to fully power the sensor’s processing and communications requirements. In others, the energy may not be available when it’s needed: e.g. no solar energy at night. However, these problems can usually be averted because typically IoT sensors do not have to gather data continuously. If so, a viable solution can be based on sensor electronics that sleep most of the time and awaken to process a burst of data from the sensor. Meanwhile, the harvesting device accumulates energy continuously, or at least whenever the ambient supply is available. The success of such schemes depends upon providing a storage medium suitable for collecting the energy harvesting device’s output. .

A supercapacitor or ultracapacitor, is a high-capacity device with higher capacitance values, but lower voltage limits, than other capacitors. It typically stores 10 to 100 times more energy per unit volume or mass than electrolytic capacitors, can accept and deliver charge much faster than batteries, and tolerate many more charge and discharge cycles than rechargeable batteries. However, the supercapitor has low energy density and voltage output from each cell, while requiring sophisticated electronic control and switching equipment. It can also be prone to excessive self-discharging, wasting much of the harvested energy.

If a rechargeable battery storage solution is preferred, Li-ion is the most popular choice for high-density, higher-voltage IoT applications. While other options such as lithium-ion polymer (li-polymer) are available, there are no real game-changers in the market, despite much research around the world.

However, there is optimism for improvement. For instance, Dyson has invested $15 million into Sakti3, a company whose solid-state battery technology promises cheaper, safer, more reliable, energy-dense, and longer-lasting products. Meanwhile, existing batteries technologies can go further using an improved version of the existing Li-ion chemistry. Tadiran industrial-grade batteries, for example, offer 20 years’ operating life in extreme environmental conditions, while reducing many of the problems associated with standard consumer products.

Helping to Drive IoT Further into the World

Energy harvesting and batteries will help to propel IoT deeper into the world around us.. IoT applications are just as hard at work in large infrastructure projects as they are in consumer applications such as home automation and wearable devices.

This success depends heavily on arrays of edge sensors, often in large numbers and frequently over a wide geographical area. Under these circumstances, low-cost, compact, rugged, reliable, and low maintenance edge nodes become essential. Using energy harvesting whenever possible helps achieve these objectives, by making the devices battery-free, or at least run from batteries that will last for many years before needing replacement.