Many current and future technologies require alloys that can withstand high temperatures without corroding. Now, researchers at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, have hailed a major breakthrough in understanding how alloys behave at high temperatures, pointing the way to significant improvements in many technologies. The results are published in the highly ranked journal Nature Materials.

Developing alloys that can withstand high temperatures without corroding is a key challenge for many fields, such as renewable and sustainable energy technologies like concentrated solar power and solid oxide fuel cells, as well as aviation, materials processing and petrochemistry.

At high temperatures, alloys can react violently with their environment, quickly causing the materials to fail by corrosion. To protect against this, all high temperature alloys are designed to form a protective oxide scale, usually consisting of aluminium oxide or chromium oxide. This oxide scale plays a decisive role in preventing the metals from corroding. Therefore, research on high temperature corrosion is very focused on these oxide scales – how they are formed, how they perform at high heat, and how they sometimes fail.

The article in Nature Materials answers two classical issues in the area. One applies to the very small additives of so-called ‘reactive elements’ – often yttrium and zirconium – found in all high-temperature alloys. The second issue is about the role of water vapour.

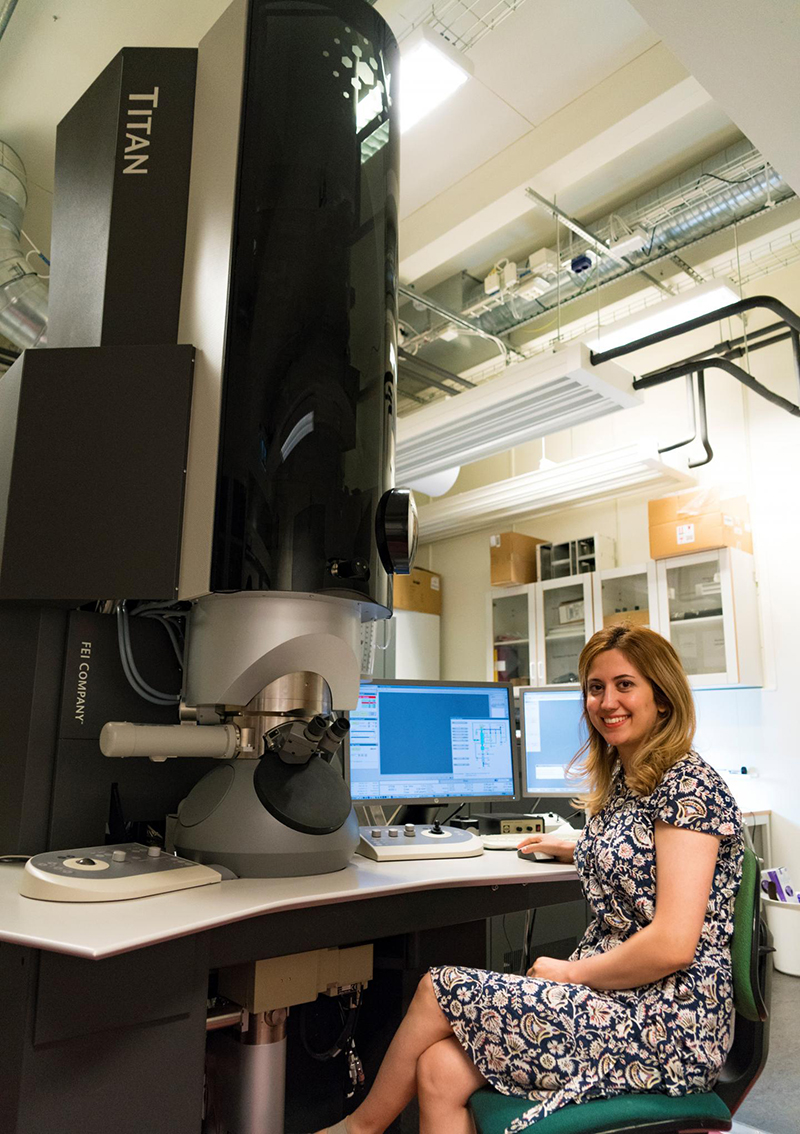

“Adding reactive elements to alloys results in a huge improvement in performance – but no one has been able to provide robust experimental proof why,” says Nooshin Mortazavi, materials researcher at Chalmers’ Department of Physics, and first author of the study. “Likewise, the role of water, which is always present in high-temperature environments, in the form of steam, has been little understood. Our paper will help solve these enigmas”.

In this paper, the Chalmers researchers show how these two elements are linked. They demonstrate how the reactive elements in the alloy promote the growth of an aluminium oxide scale. The presence of these reactive element particles causes the oxide scale to grow inward, rather than outward, thereby facilitating the transport of water from the environment, towards the alloy substrate. Reactive elements and water combine to create a fast-growing, nanocrystalline, oxide scale.

“This paper challenges several accepted ‘truths’ in the science of high temperature corrosion and opens up exciting new avenues of research and alloy development,” says Lars Gunnar Johansson, Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at Chalmers, Director of the Competence Centre for High Temperature Corrosion (HTC) and co-author of the paper.

“Everyone in the industry has been waiting for this discovery. This is a paradigm shift in the field of high-temperature oxidation,” says Nooshin Mortazavi. “We are now establishing new principles for understanding the degradation mechanisms in this class of materials at very high temperatures.”

Further to their discoveries, the Chalmers researchers suggest a practical method for creating more resistant alloys. They demonstrate that there exists a critical size for the reactive element particles. Above a certain size, reactive element particles cause cracks in the oxide scale, that provide an easy route for corrosive gases to react with the alloy substrate, causing rapid corrosion. This means that a better, more protective oxide scale can be achieved by controlling the size distribution of the reactive element particles in the alloy.

This ground-breaking research from Chalmers University of Technology points the way to stronger, safer, more resistant alloys in the future.

More about: Potential consequences of the research breakthrough

High temperature alloys are used in a variety of areas, and are essential to many technologies which underpin our civilisation. They are crucial for both new and traditional renewable energy technologies, such as “green” electricity from biomass, biomass gasification, bio-energy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), concentrated solar energy, and solid oxide fuel cells. They are also crucial in many other important technology areas such as jet engines, petrochemistry and materials processing.

All these industries and technologies are entirely dependent on materials that can withstand high temperatures – 600 ° C and beyond – without failing due to corrosion. There is a constant demand for materials with improved heat resistance, both for developing new high temperature technologies, and for enhancing the process efficiency of existing ones.

For example, if the turbine blades in an aircraft’s jet engines could withstand higher temperatures, the engine could operate more efficiently, resulting in fuel-savings for the aviation industry. Or, if you can produce steam pipes with better high-temperature capability, biomass-fired power plants could generate more power per kilogram of fuel.

Corrosion is one of the key obstacles to material development within these areas. The Chalmers researchers’ article provides new tools for researchers and industry to develop alloys that withstand higher temperatures without quickly corroding.