Part 1 of this FAQ looked at the application and operating principles of the magnetron. This part explores the development and special history of the device, as well as disruptive alternative technologies for some applications.

Q: What’s the history of the magnetron?

A: The development and production of the magneton was a major advance during World War II. Prior to the magnetron, power oscillators for radar could only operate to about 100 to 300 MHz ) – now considered to be a low-end RF frequency, but not in the 1930s and 1940s – which meant long wavelengths, poor reflected-signal resolution, and physically large antennas.

The magnetron operated at over 1 GHz and enabled radar systems which were far smaller and could use a modest-size parabolic antenna which could be fitted into the nose of aircraft, on ships, and even submarines, in addition to land-based systems. In addition, the shorter wavelengths gave a much higher resolution. Magnetron-based radar was a key element in the British victory in the skies during the Battle of Britain against German planes, and in ship operations against other ships and even U-boat submarines as their periscopes could be spotted via radar.

Q: How did this enhanced come about?

A: The history of the magnetron development, implementation, and the role has been extensively covered and recounted in books and articles. In brief, the first crude unit was developed in the 1920s by an American engineer working at General Electric, and in 1934, the cavity magnetron – the first-generation of “modern” version – was developed at the legendary Bell Telephone Laboratories.

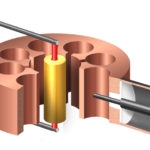

But the cavity magnetron was not ready for widespread use: it was large, inefficient, and unreliable. All that changed in 1939, when two British physicists at the University of Birmingham (UK) produced a prototype of a much-improved version (Figure 1). However, it was complicated to machine from a block of metal. Still, it produced over 400 watts of power at the extremely short wavelength of 9.8 cm (about 4 inches). This was nearly a hundred times more power than anyone else had ever produced at that wavelength.

With Britain already at war, a single prototype of this magnetron was carried to the US as a top-secret device. Engineers and scientists at the MIT Radiation Laboratory in Cambridge (Massachusetts) – the site of most WWII electronic R&D – studied it and, among other enhancements, devised a way to improve its production-related design (using welded vanes rather than difficult machining) to where it became much easier to make, lighter, and had improved performance as well. This manufacturable design became the core of WWII radar sets, which were produced and installed by the tens of thousands and represented a major “secret” asset in Allied war effort. These magnetrons were compact – about the size of a large fist – yet produced hundreds of RF watts.

Q: What does such an early magnetron look like?

A: Figure 1 shows the core of the CV64, a widely used early magnetron. It does not show the magnet assembly or electrical connectors, or the associated circuitry.

Q: Are there any other interesting aspects of the magnetron?

A: Anther turning point came in the late 1940s. When an American engineer at Raytheon found that microwaves produced by the magnetron at the certain frequencies could heat and cook food. The first commercial microwave ovens – which were large and extremely costly – reached the market in the late 1950s. Now, of course, you can get a magnetron-based based microwave oven that fits on a tabletop for under $100.

Q: What frequency is used for cooking in a home microwave oven?

A: Consumer ovens operate at 2.450 MHz, the frequency which causes dielectric heating of the water molecules in the food (commercial microwave ovens used for cooking and drying operate at lower frequencies such as 900 MHz, for various reasons). Note that the 2.450-MHz value is in the middle of one of the lower-frequency unlicensed ISM (industrial, scientific, medical) and Wi-Fi RF band allocations, which means that a home microwave oven can interfere with Wi-Fi and other wireless links.

Q: What does a consumer microwave oven magnetron look like?

A: Due to the high volume of production, these designs have evolved and are focused on low cost, compactness, and simplicity (Figure 2).

Q: What’s the future of the magnetron-based microwave oven for consumer ovens?

A: The are major efforts underway to replace the magnetron with solid-state power amplifiers (SSPAs). Among the reasons: the output power of the standard microwave oven is hard to control, as it must be pulse-width modulated at a slow rate, with tens of seconds on then off) and so does not apply constant heating. It also produces and uneven RF field and thus uneven heating. Efficiency is also low.

In principle, ovens using SSPAs would use an array of distributed units and offer continuous analog control of the power level. Further, the frequency of the SSPA microwave oven could be adjusted as needed for optimal performance. The SSPA-based oven would have a temperature and power sensors to close the feedback loop for control and more accurate performance compared to the open-loop magnetron-based oven.

Note that SSPAs are already used in commercial microwave drying ovens, for example, where their greater efficiency and controllability make them cost-effective. For consumer ovens, however, the cost pressures are more intense, and it is unclear when these SSPA-based ovens will on the market since most consumers appear satisfied with magnetron units. SSPA microwave ovens for high-end home kitchens may be the first to adopt these newer microwave ovens. Perhaps they will have a special label on their door saying “SSPA” just as the first transistor radios proclaimed “all transistor” on their front panels.

Q: Who is active in developing and promoting SSPAs for consumer ovens and solid-state cooking (SSC)?

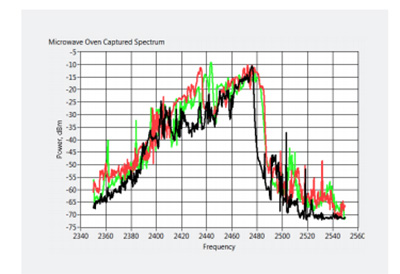

A: Netherlands-based Ampleon is one of the sources which is developing these products. Their lengthy white paper “RF Solid State Cooking” provides many details with specifications, graphs, and thermal images on the performance and shortcomings of magnetron-based ovens, and the apparent advantages of SSPAs and SSC. For example, it shows the surprising variability of a magnetron-based oven on multiple “identical” runs, (Figure 3).

Although the magnetron no longer has the critical role in radar and other functions it once had, it has transitioned from a vital WWII secret to the core component of a mass-market microwave oven in the decades since its development. As part of its development, it has also spurred insight and experience related to other specialized RF/microwave vacuum tubes, some of which are still used. The days of the magnetron may be nearing an end as solid-state power amplifiers come down in price, but it is hard to displace a product that a consumer can buy starting at under $100, even if there are performance issues.

EE World Online References

- Basics of cavity resonators

- Basics of waveguides, microwaves, and ovens

- Passive microwave components, Part 1: isolators and circulators

- Passive microwave components, Part 2: couplers and splitters

References

- Wikipedia, “Cavity Magnetron” (has links to many historical references)

- Explain That Stuff, “How Magnetrons Work”

- Georgia State University, Hyperphysics, “The Magnetron”

- Georgia State University, Hyperphysics, “Microwave Ovens”

- Microwaves101, “Magnetrons”

- Engineering and Technology History Wiki, “Cavity Magnetron”

- The Valve Museum, “CV64”

- Lamps & Tubes, “CV64 Early British S-band Cavity Magnetron”

- Radar Tutorial EU, “Magnetron”

- Ampleon N.V., “RF Solid State Cooking”

- ARMMS RF and Microwave Society, “Summary of Magnetron Development”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.