Analog color TV is now obsolete, but the story of its development shows both the power and fragility of market dominance.

The ubiquitous presence and dominant positions of Facebook, Amazon, Apple, and Google in our lives – for good and bad – make it logical to think that these companies will be around “forever” and continue to have such overwhelming roles. But while history does not necessarily repeat itself, it also teaches us that such dominance may not last, even for companies that have comparable stature.

How so? Just three decades ago, the pundits said our lives would be controlled for the foreseeable future by the trinity of IBM PCs using Intel processors and running the Microsoft Windows operating system. Fast forward to the 21st century, and IBM is completely out of the PC business, Intel is still a major player but has intense competitors in new markets, and while Windows is still a leading OS, it is certainly not the only one that matters. Right now, there’s General Electric (GE), which has fallen on tough times after 100 years with well-known commercial, industrial, and consumer businesses.

The story of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) shows that an overwhelming market position is rarely secure. With the transition to digital broadcast TV over the past decade, it’s easy to forget the color TV standard that served us well for over five decades, and how it came about. It’s a story of engineering and production innovation across many dimensions, of extremely clever, all-analog signal encoding techniques, of spending billions in corporate money, and finally, of unarguable success. It’s also the story of one man – David Sarnoff – who was determined to make it happen, regardless of effort, innovations, or costs, and who achieved his dream. It’s also a story of corporate dominance and eventual disappearance.

Sarnoff, born in 1891, came to America as a poor Jewish immigrant boy and worked his way up through dedication, luck, self-promotion, and more. He joined the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America in 1906 and moved from office boy to commercial manager of the company in just eleven years, along the way gaining hands-on experience installing the new technology called “wireless” on ocean-going ships. He even spent on time some of them as the radio operator. (As a young man, he was reportedly one of the telegraph operators in New York who received messages from the Titanic in 1912 as she sank, but this is unprovable.)

General Electric bought Marconi in 1919 and transformed it into the Radio Corporation of America (RCA); soon after, it was split off, and by 1930, Sarnoff was company president (Figure 1), remaining there until his retirement in 1970 (he died a year later). Although a public company, RCA was run almost as a fiefdom by the autocratic Sarnoff.

What was RCA in its glory days? While RCA is primarily now a licensed marketing nameplate, in the mid- and late-20th century, it was one of the most respected and dominant (and sometimes feared) companies in electronics. Think of it as Intel, IBM, and Microsoft rolled into one at the peak of the PC business. The company was a major factor in music records and record players (RCA Victor, Victrolas), military, aerospace, satellites, and broadcast markets. In almost any application which involved “electronics,” RCA was there. The RCA logo, and that of RCA Victor was as well-known worldwide as that of McDonald’s is today (Figure 2a and 2b).

RCA didn’t just design, manufacture, and sell a breadth of products; they also designed and built many of the components used within them in their own factories, such as the vacuum tubes (and sold them on the open market, as well). They had their own R&D labs (not as well known as AT&T’s Bell Labs, but still impressive), and owned and operated factories to press the records for their RCA Victor record label. They also owned NBC, the National Broadcasting Company. They were vertically integrated to an extent that is rarely seen today, and they invested heavily in design, production, and promotion.

Although not an engineer, Sarnoff was technically knowledgeable and smart enough to recognize good ones when he saw them. He hired and funded R&D engineers, such as Vladimir Zworykin, a leading innovator in photomultiplier tubes (a core element of TV cameras). He was also one of the few to recognize early on that radio could be a mass-broadcast medium for voice and music, rather than just a point-to-point communications link for public safety.

Although not an engineer, Sarnoff was technically knowledgeable and smart enough to recognize good ones when he saw them. He hired and funded R&D engineers, such as Vladimir Zworykin, a leading innovator in photomultiplier tubes (a core element of TV cameras). He was also one of the few to recognize early on that radio could be a mass-broadcast medium for voice and music, rather than just a point-to-point communications link for public safety.

But analog TV is gone.

By 1950, monochrome (black and white, or B&W) TV based on the EIA RS-170 monochrome standard (first publically demonstrated in 1938) was starting to take hold in households. Visionaries dreamed of a full-color system, but no one knew how actually to create one. The only thing everyone agreed on was that you could create full-color images by combining red, green, and blue primary colors. Beyond that, there was no agreement on the path to color TV and no road map. Still, consumers assumed that since movies went to color in the 1930s and 1940s, the TV should be able to do the same — even though the problem and solutions are very different.

RCA and NBC did have a broadcasting archrival: CBS, the Columbia Broadcasting System, headed by William S. Paley. Sarnoff viewed CBS as “just a broadcaster” (what we now call a “media company”) with little technical expertise, minimal engineering innovation, a small R&D effort, and no manufacturing (partially but not entirely true – CBS developed the long-playing 33 1/3 rpm vinyl record, a significant achievement). CBS primarily produced or bought shows to broadcast, in contrast to RCA and NBC’s full menu, which included TV receivers, broadcast-studio equipment, and components engineering in addition to the content.

Adding to the animosity was that Paley was from an upper-crust family while Sarnoff had worked his way up from penniless. Paley was invited to all the “right” social events, and CBS prided itself as being the high-tone “Tiffany Network.” The rivalry between the two companies and their leaders was both business and personal.

A mechanical color TV?

Does ancient analog color-TV matter? Many of the principles and characteristics of analog color TV are still embedded, although not apparent, in our digital-TV world. CBS did, in fact, offer a prototype system that could do color in the 1930s. It used a spinning wheel divided with red, green, and blue filter segments, and the rotation of the wheel was synchronized with a similar wheel at the TV camera. In this way, a single monochrome camera and corresponding cathode ray tube (CRT) could display a moving color image. This approach (which was even used in some early space shots, due to better resolution and lower power needs than the conventional color imager) had several mass-market shortcomings, although it was demonstrated ahead of the RCA version:

- the filter wheel had to be at least twice the size of the screen

- the receiver’s filter wheel had to be precisely synchronized with the camera’s wheel

- it was mechanical, and so makes noise and has reliability issues.

- the format was incompatible with the millions of monochrome TV sets in use, although there was a scheme to make an add-on kit.

Nonetheless, the CBS system was ready by 1940, while RCA’s design had a very long way to go. In fact, the CBS-system picture than looked far better in early match-ups against RCA’s first crude demonstration in the late 1940s.

Still, Sarnoff and RCA would have nothing to do with the CBS approach and derided it for what it was: a stop-gap attempt to make color TV possible, but a dead-end solution. Instead, he vowed to develop an all-electronic color system that was compatible with the B&W units already in homes. Much like President Kennedy’s vow to land a man on the moon by the end of the decade without mention of cost, Sarnoff and RCA went after color TV with an open-ended budget. Though it is hard to put a solid number on the development cost, estimates are that RCA spent between $150 million and $200 million of their own money (yes, they funded it themselves) on the project by 1960 — and that’s in 1950s dollars, so it is at least 10 or 20 times that amount in today’s dollars.

The effort was orders of magnitude more complicated than just coming up with a viable scheme to do it, which would be marked “complete” with a basic feasibility demonstration. Instead, it would require developing, perfecting, and building in volume the needed technologies (imagers, CRTs, and more), the broadcast chain, and saleable end products. For any new components, they also developed new manufacturing techniques and built factories to manufacture them.

It also needed a color-TV ecosystem. Since RCA owned NBC, they were able to force an answer to the innovator’s “which comes first?” dilemma: why upgrade all those broadcast facilities at major expense, if no one has a color TV set at home? But why buy a color TV set if no stations are broadcasting in color?

Part 2 of this article looks at the forward- and backward-compatible solution that RCA devised and implemented, as well as the company’s decline.

EE World References

Teardown: Retro Portable CRT TV

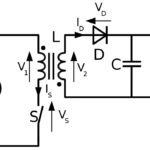

Flyback power converters, Part 1: Basic principles

Flyback power converters, Part 2: Enhancements and ICs

Working with higher voltages, Part 1: Voltage boosters

Working with higher voltages, Part 2: Voltage multipliers

Cathode ray tube vs. flat screen displays in oscilloscopes

External References (and there are many, many more covering the business aspects, color TV development, RCA history, timelines. technology, circuits, components, and consumer TV receivers)

- David E. Fisher and Marshall Jon Fisher, “Tube: The Invention of Television” (excellent overview book)

- Eugene Lyons, “David Sarnoff, a Biography”

- The David Sarnoff Library

- Ken Burns, “Empire of the Air: The Men Who Made Radio,” (PBS Video)

- Tom Lewis, Empire of the Air: The Men Who Made Radio,” (companion to PBS video)

- Kenneth W. Bilby, “The General: David Sarnoff and the rise of the communications industry”

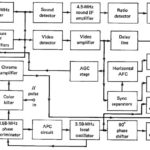

- com, “Color Television Receiver Block Diagram”

- Vocal Technologies, “Analog TV Standards”

- Wikipedia, “Color TV”

- Wikipedia, “NTSC”

- Science Direct, “Chrominance”

- 1000Logos, “RCA”