Part 1 examined a major technical problem of the 19th century: improving the efficiency and reach of the lighthouse beam, and why simply going “bigger” would not be possible.

A new way of seeing the problem

New ideas were needed, and the French government in the early 1800s was aware of the problem, even linking lighthouses and their range to the needs of the French empire. Emperor Napoleon I (Napoleon Bonaparte) had a technical degree with an emphasis on mathematics and encouraged advances in science and engineering for military and commercial gain. The government established a commission to investigate the lighthouse issue and established a contest with substantial rewards for tangible improvements.

That’s where French engineer, physicist, and mathematician Augustin-Jean Fresnel (in those days, many of the technical elite had expertise in multiple areas) resolved the problem with a compact lens he developed in the early 1820s specifically for lighthouses. His lens used a series of concentric sub-lenses with “stepped” radii and resulted in an overall lens which was far thinner and lighter, yet was almost as efficient as a standard lens. Within a few years, his innovation was the only lens in use.

Fresnel (pronounced Fre-nel, the “s” is silent) (Figure 1), was born in 1788, graduated from the prestigious National School of Bridges and Highways, and had done significant fieldwork designing and overseeing many installations. He was also hands-on as needed since getting the skilled labor who understood what he wanted to be done was a challenge, especially in rural areas. He did not enjoy social events, preferring to work out problems rather than attend society gatherings. Fresnel had wide interests: he had already devised a new process for making soda ash, a critical component in the manufacture of glass, textiles, soap, and paper; the process, with some changes, eventually resulted in the development of the highly profitable Solvay process in Belgium in the mid-1860s.

His interests in physics led him to study the nature of light. In the early 1800s, light was defined by Newton’s theory and believed to consist of weightless, and tiny particles called the “corpuscular” concept. Fresnel studied one area where this corpuscular of light did not hold up and which contradicted Newton: the diffraction of light and the resultant fringes and patterns. Fresnel suggested that light had a wave nature, and these waves could interfere constructively or destructively with each other. This would explain easily observed effects such as alternating bands of light and dark in the basic double-slit experiment. Note that these two conflicting views of the inherent nature light spawned decades of dispute between adherents on both sides, until quantum theory in the early 1920s postulated light’s particle/wave duality characteristics, and showed that these are not contradictory attributes.)

Fresnel’s innovation: idea meets implementation

While open bonfires were first used for navigation markers, they were eventually enhanced with simple flat mirrors as reflectors, then spherical bowl mirrors, and finally, parabolic reflectors. Since it was not possible to make large parabolic reflectors, many installations use a stack of smaller ones. Even these enhancements had only minor benefits, as it was hard to align the stacked reflectors, and the light source had to be precisely placed at each focal point for it to work well. The reflectivity was moderate as well, with about 50% of the light lost in the mirror.

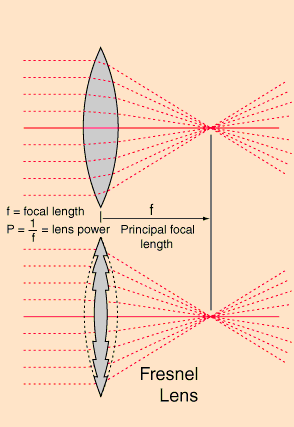

A lens would be better than reflector as it loses only 5 to 10% of the light in transmission. But the lens needs to be close to the source to actually capture the rays, with a short focal length and large refraction angle, to yield a parallel beam. A sharply curved lens could be placed further away but would be very large and thick.

Fresnel realized that he could create a very large lens, but without all the bulk, by constructing it as a series of stepped lenses (Figure 2). The plan was to use multiple concentric sections (rings), consisting of carefully shaped prisms. Each ring would bend the light it captured; working together, they would create the large parallel beam. Since the ring idea was not possible to cast or form in practice, he decided to use small polygon prisms. There were problems with glue melting due to heat from the lamp, so he had to use fish-based glue that had fortunately been developed at the same time. The prisms were a plano-convex design, flat on one side, curved on the other.

Of course, an idea is one thing, while making it happen is another. Glass-making, casting, and polishing in the early 1800s was a relatively crude process, and material purity and consistency were major issues. Flint glass was the first choice due to its high index of refraction and optical clarity but is much heavier than other glasses. Instead, Fresnel and the factories he worked with had to use crown glass, which could be molded more easily than flint glass; however, due to its lower refractive index, it had to be thicker for the same effect.

Part 3 looks at how the basic Fresnel lenses were fabricated and then its performance in the lighthouse application was further improved.

EE World Online References

Flat-pack lens boosts solar power

Minuscule, Flexible Compound Lenses Magnify Large Fields Of View

Novel Nanotechnology Technique Makes Table-top Production Of Flat Optics A Reality

Enable Machine Learning with an Advanced Motion Detector Using PIR Sensors

Physicists Create Star Trek-Style Holograms

Related Content and References:

- “A Short Bright Flash: Augustin Fresnel and the Birth of the Modern Lighthouse,” Theresa Levitt, W.W. Norton & Co., 2013

- “Fundamentals of Physics,” Halliday and Resnick, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Encyclopædia Britannica , “Augustin-Jean Fresnel”

- Wikipedia, “Fresnel lens”

- “Fresnel Lens

- Hyperphysics/Georgia State University, ” Fresnel Lens”