The ocean liner S.S. United States was super sleek, extremely fast, and highly engineered…yet soon became obsolete due to air travel; cruise ships are now the royalty of the seas.

When we see the grand days of ocean liners in old movies or documentaries, they present images of elegance and sophistication through their furnishings, decor, formal dinners, and dress, but do not evoke technical innovation.

This isn’t surprising, as the extreme hazards of ocean travel dictate use of cautious, proven design rather than change and risk. Today’s cruise ships, which are designed as apartment buildings tipped on their sides and sporting Disney-like entertainment with guests wearing shorts and flip-flops, fulfill a very different function of entertainment rather than the ocean-going transportation role of the ill-fated Titanic, Ile de France, Queen Mary, or Queen Elizabeth, to cite a few of the classic liners.

But even among the ocean liner’s glory and glamour days, one ocean liner stands out: the S.S. United States (Figure 1). Although not considered to be the most opulent of the grand liners (though it was among the top), it had attributes that the others could not match: sheer speed coupled with amazingly graceful lines. On her maiden voyage between Cornwall, UK, and New York, she easily broke the long-established speed record, taking about 3½ days each way (and the ship still holds these records in its class).

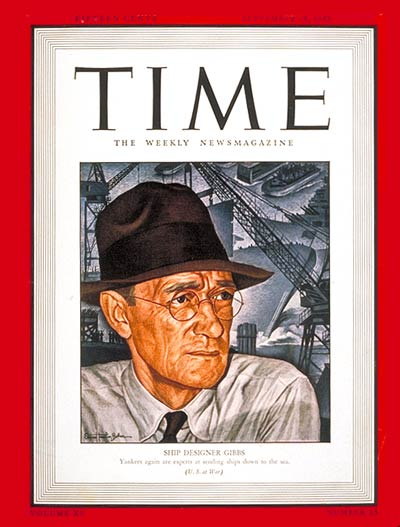

Its entire design from hull geometry, to mechanical issues such as power plant and ventilation, soft features such as furnishings, and critical safety aspects were conceived of and driven by William Francis Gibbs, born in 1886 (Figure 2). Gibbs was an experienced naval architect, of course, but entirely self-taught with no formal training; in fact, he had a law degree in 1913, but left law after winning his first and only case.

Enamored of ship design, he studied on his own for over a year, then won a bid for a trans-Atlantic ship in partnership with his brother, which they completed on time and under budget. During World War 1, he did major design work for the Navy, which enhanced his skills and his reputation.

He also studied the main causes of ship sinking and loss of life, primarily collisions and fires, and became obsessed (in a good way) with reducing the occurrence and impact of those calamities. While he could not directly reduce collisions, he could minimize their effects with better design, better use of watertight compartments (the ones on the Titanic allowed water to flow over each compartment’s bulkhead into the next compartment, therefore canceling the “watertight” aspect). Gibbs included extra safety factors into one of his next major designs (the Malolo), which was accidentally rammed on its maiden voyage; she survived and made it back to port despite a major gash in the hull, which further solidified his reputation.

Still, Gibbs felt fire was the real issue to minimize on a ship, and which frequently occurred due to open flames, combustible materials, wood decking, cigarettes and cigars, steam boilers, and more, and situated everywhere. He saw the calamitous results of a fire in 1934 aboard the Morro Castle just a few miles off the shore of New Jersey, which took over a hundred lives as people on the shore watched helplessly when the ship caught fire and quickly burned. Gibbs felt that compared to a collision or even sinking, a fire at sea was more terrifying and lethal since it spread so fast and induced panic, so he focused on building a fireproof ocean liner.

The reality of World War II interrupted his dream, as Gibbs worked on destroyer design and became lead designer for the mass-produced Liberty ships. He was a key driver in adopting the production techniques of the auto industry to the traditional method of shipbuilding by having major subassemblies pre-fabricated off-site, rather than building everything up from individual parts at the less-efficient shipyard environment.

Part 2 discusses some of the design, engineering, and production innovations of the S.S. United States.

EE World References

“Electric locomotives and catenary power systems – Part 1: basic functions”

“RCA & Color TV: A dominant company and standard, both now gone – Part 1”

“RCA & Color TV: A dominant company and standard, both now gone – Part 2”

External References

- Steven Ujifusa, “A Man and His Ship: America’s Greatest Naval Architect and His Quest to Build the S.S. United States,” Simon and Shuster, 2012

- Steven Ujifusa on William Francis Gibbs and His Ships (podcast and transcript)

- SS United States Conservancy , especially the link “The Ship”

- Vox Media, Curbed NY, “Deadline Looms for Historic Ocean Liner’s Move to Brooklyn”

- Cruise Maven, “Crystal Cruises Hopes to Return S.S. United States to Oceangoing Service” (2016)

- Cruise Mapper, “Cruise Ship Design Construction Building”

- Maritime Cyprus, “Ovation of the Seas Floated Out At Meyer Werft Shipyard”

- Cruise Mapper, “Deck Plans”

- Cruise Mapper, “Cruise Ship Engine Power, Propulsion, Fuel”

- The Telegraph, “13 things you didn’t know about cruise ship design”

- Interesting Engineering, “Understanding the Incredible Engineering of Cruise Ships”

- GCaptain, “Ship Engines – 7 Monster Engine Designs, Part 1”

- Carnival Corp., “The Design and Construction of a Modern Cruise Vessel”

- Martin Ottaway, “The Delightful Frustration of Cruise Ship Power Plant Design”