Most EEs probably think of a Fourier transform in terms of an operation that converts time-based waveforms on a scope into their component frequencies. But Fourier transforms also play a role in infrared spectroscopy.

It might be easiest to explain Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy by contrasting it with conventional spectroscopy. Also called “dispersive spectroscopy,” the conventional technique is to shine a light beam having a single wavelength at a sample, then measure how much of the light is absorbed. The process then repeats for each different wavelength of interest.

In contrast, FTIS doesn’t use monochromatic (single wavelength) light. Instead, it bathes the sample in a light beam containing many frequencies of light simultaneously and measures the amount the sample absorbs. Next, the beam is altered to contain a different combination of frequencies, and the absorption is again measured for a second data point. This process repeats rapidly. A computer then takes all this data and works backward to infer the absorption at each wavelength.

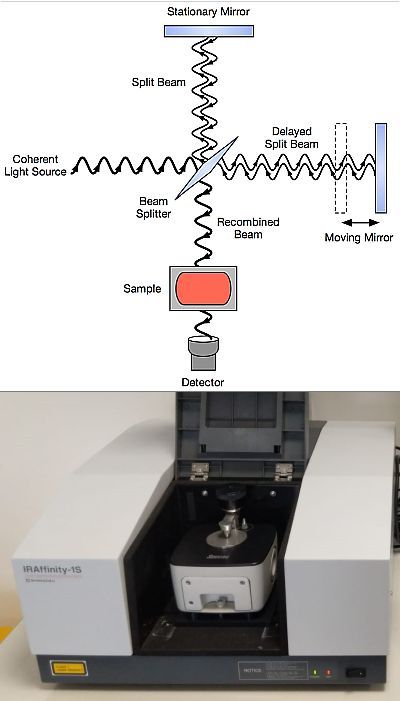

The polychromatic beam used in FTIS is generated by starting with a broadband light source that contains the full spectrum of wavelengths to be measured. This light shines into a Michelson interferometer. The interferometer consists of a beam splitter, a movable mirror and a fixed mirror, and a detector. In operation, the polychromatic beam hits the beam splitter where half the light continues traveling to a movable mirror, the other half to a fixed mirror angled 90° from the original beam. Light reflects from the two mirrors back to the beam splitter where some fraction of the original light reflects on to the sample. Light leaving the sample then gets refocused on to a detector.

The point of making one of the mirrors movable is to set up wave interference with specific light wavelengths from the polychromatic source. As this mirror moves, interference periodically blocks and transmits each wavelength of light in the beam. Different wavelengths are modulated at different rates, so at each moment or mirror position the beam coming out of the interferometer has a different spectrum.

Fourier transforms are used to turn the raw data (light absorption for each mirror position) into the desired result (light absorption for each wavelength). As is the case for scope displays of signal frequency, the Fourier transform converts one domain (in this case displacement of the mirror in centimeters) into its inverse domain (wavenumbers in cm−1). The raw data is called an interferogram.

Many of the benefits of the FTIS technique arise from the fact that all wavelengths are collected simultaneously. This brings a higher signal-to-noise ratio for a given observation scan-time. Alternatively, it allows a shorter scan-time for a given resolution. In practice multiple scans are often averaged, boosting the signal-to-noise ratio by the square root of the number of scans.

Also, FTIS apparatus allow more light to hit the sample for a given resolution and wavelength compared to dispersive instruments. The reason: dispersive spectrometers contain a monochromator used to mechanically select narrow bands of light. It has entrance and exit slits which restrict the amount of light passing through. Although FTIR spectrometers have no slits, they require an aperture to restrict the convergence of the collimated beam in the interferometer because convergent rays are modulated at different frequencies as the path difference varies. For a given resolution and wavelength this circular aperture (called a called a Jacquinot stop) allows more light through than a slit, resulting in a higher signal-to-noise ratio.

FTIS tend to be more accurate than dispersive instruments because their wavelength scale is calibrated by a laser beam of known wavelength that passes through the interferometer. In practice, FTIS accuracy is limited by the divergence of the beam in the interferometer which depends on the resolution. In contrast, dispersive instruments use a wavelength scale that depends on the mechanical movement of diffraction gratings.

Finally, in dispersive instruments stray light can arise from imperfections in the diffraction gratings and accidental reflections, radiation of one wavelength appearing at another wavelength in the spectrum. FTIS don’t have this problem because the apparent wavelength is determined by the modulation frequency in the interferometer, not by a diffraction grating.