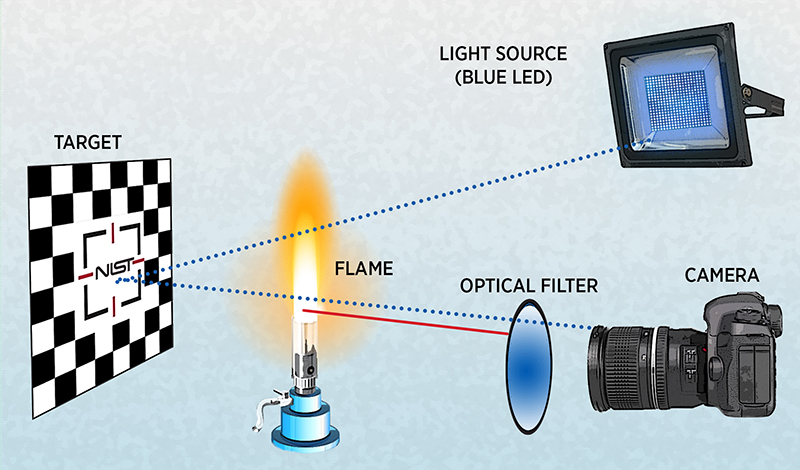

Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have demonstrated that ordinary blue light can be used to significantly improve the ability to see objects engulfed by large, non-smoky natural gas fires—like those used in laboratory fire studies and fire-resistance standards testing.

The NIST blue-light imaging method can be a useful tool for obtaining visual data from large test fires where high temperatures could disable or destroy conventional electrical and mechanical sensors.

The method provides detailed information to researchers using optical analysis such as digital image correlation (DIC), a technique that compares successive images of an object as it deforms under the influence of applied forces such as strain or heat. By precisely measuring the movement of individual pixels from one image to the next, scientists gain valuable insight about how the material responds over time, including behaviors such as strain, displacement, deformation and even the microscopic beginnings of failure.

“Fire makes imaging in the visible spectrum difficult in three ways, with the signal being totally blocked by soot and smoke, obscured by the intensity of the light emitted by the flames, and distorted by the thermal gradients in the hot air that bend, or refract, light,” said Matt Hoehler, a research structural engineer at NIST’s National Fire Research Laboratory (NFRL) and one of the authors of the new paper. “Because we often use low-soot, non-smoky gas fires in our tests, we only had to overcome the problems of brightness and distortion.”

To do that, Hoehler and colleague Chris Smith, a research engineer formerly with NIST and now at Berkshire Hathaway Specialty Insurance, borrowed a trick from the glass and steel industry where manufacturers monitor the physical characteristics of materials during production while they are still hot and glowing.

“Glass and steel manufacturers often use blue-light lasers to contend with the red light given off by glowing hot materials that can, in essence, blind their sensors,” Hoehler said. “We figured if it works with heated materials, it could work with flaming ones as well.”

For rest of the story click here.