Despite wide use of “soft” on/off switching, the traditional electromechanical switch is still often required or preferred and is available in countless versions.

Let’s look at some available switch styles.

1) The knife switch It doesn’t get simpler than the knife switch. The first and simplest switch is the knife switch (Figure 1). This style is now only used in specialized industrial applications due to its open and exposed contacts. It was – and still is – a staple of movies where the “mad scientist” dramatically “throws the switch” to bring the monster to life; you can even buy realistic-looking plastic ones to use as “props” in a film).

It is available in that basic SPST configuration as well as the widely used DPDT version (Figure 2). Both are still used in introductory science and electricity kits due to their simplicity and making the switching function obvious, measurable, and tangible.

Special versions are also available, such as a three-pole single-throw model with built-in fuses (Figure 3). The latter version is for high-current, high-voltage situations.

Since all the conducting elements of the knife switch are exposed, there are serious safety issues if used for high voltages or currents. Even if only handling a safe, low voltage, it is obviously “open” to accidental touching and thus short circuits.

Other switch types match application needs

The knife switch is rarely used anymore for obvious reasons, but many other switch styles are widely used. Each has its role for technical, traditional, or user-appeal reasons, and for each basic style, there are many available sub-styles.

We’ll take a brief look at some of the broad classes. In general, each switch type is available for applications ranging from low voltage/current (tens of volts, around one amp) to AC line voltage/current (120/240 VAC, 15-20 amps) and much higher. Many are also offered in the basic SPST arrangement as well as SPDT, DPST, and DPDT configurations, in the same or slightly different body sizes.

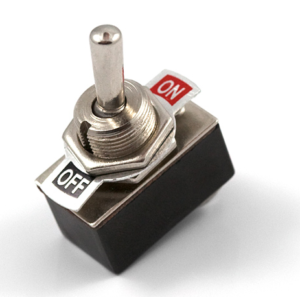

2) The toggle switch The toggle switch (Figure 4) has an extended handle that is used to flip it from the on to off position or vice versa. While some are silent or fairly quiet, others are designed to give a clear, satisfying “click” when they are toggled in either direction.

The round “handle” is most common, but flat paddles and other handle styles are also available to fit the application’s aesthetics. The widely used basic AC-light switch (Figure 5) is an SPST toggle switch, while its sibling, the “upstairs/downstairs” light switch, is an SPDT version in the same size housing.

Most non-consumer toggle switches require a round hole, which is less costly to fabricate (and easier for porotypes and do-it-yourself) than some of the other switch types. It also means that getting a replacement toggle switch that fits – or can be made to fit – is not difficult since mounting holes can be enlarged to some extent or made smaller using washers; this is beneficial when repairing older or damaged equipment.

Some toggle switches offer a three-position double-throw operation called on-off-on, where contacts are made in either direction of the toggle. Still, there is also a central “neutral” position where no contact is made. This is useful where the design needs a switch setting that allows for two choices of current-flow path or no flow at all.

3) The rocker switch Rocker switches replace the toggle handle with a see saw-like rocking actuator (Figure 6). They allow for a lower profile on the product panel, and they can actuate by a push-down action rather than a swipe up or down the handle, as needed by the toggle. In some cases, the rocker offers preferred esthetics for the user, while in other cases it provides a more convenient on/off action.

Most rocker switches require a square cutout in the panel (round ones are also available but less widely used) and more “surface area” than toggle switches. Still, the actuator part can be labeled, eliminating the need for a panel label in some cases, thus saving space.

Rockers also have a sleeker look, and many toggle switches for lighting in homes in the US now use them (Figure 7). Regardless of intended use, rocker switches are available with contact ratings from low voltage and current the same as those available for toggle switches.

Some rocker switches offer internal illumination, turning on/off independent of the switch position (Figure 8). This provides feedback to the user as to the effect of the switch action and is widely used on AC-line applications such as power strips.

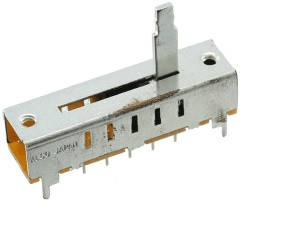

4) The slide switch Slide switches are widely used in many products and require a rectangular cutout (Figure 9). If panel-mounted, they may also require a screw on each side to attach them to the panel or to the circuit board underneath (although PC-board-mount versions are also available). One of their characteristics is that they are somewhat harder to accidentally “flip” by brushing against or bumping into them.

Slide switches are also available with more than two positions, such as this through-hole, PC-board mounted, four-position slide switch, which can be used to set a visually intuitive “off-low-medium-high” speed for an appliance (Figure 10).

5) The alternate-action switch Unlike the preceding switches, the on/off alternate-action switch looks like a round or square momentary-contact pushbutton switch (Figure 11), so its status cannot be determined at a glance. It is used when the product design calls for the user to use a push-on/push-off action or when panel space is limited.

It is a push on-push off switch in that pushing it once makes and latches the connection, while pushing it again breaks it, usually with a very audible click both times; this is called push-push (Figure 12).

Some applications prefer that the user not be able to undo the switch-on action easily, so their alternate-action cycle requires a push-down to activate but a “lift-up” to deactivate; this is a push-pull alternate-action switch (Figure 13).

There’s also a pull-pull alternate-action switch, often used in light fixtures, where you pull a string or chain to turn the lamp on and then off.

To overcome the inability to visually judge the switch position in cases where that is needed, many alternate-action switches also are offered with an internal light which is usually wired to turn on when the switch is in “on” position or when the action the switch is presumed to initiate has been carried out (Figure 14).

Finally, there’s the well-known, dramatic “emergency” alternate-action switch used in safety-related situations to allow an operator to cut power quickly (Figure 15). This mushroom-top switch stands out by design and is usually located in a clear, open area where it can be reached easily. Pushing it once cuts power, while pushing it again restores power.

Some of these emergency switches are used in mechanically linked pairs for the alternate action, with one for power on and the other for power-off (Figure 16).

Finally, a note about switch ruggedness. Nearly all the switch types are available in a range of electrical and mechanical roughness ratings. These include low-end consumer switches with almost no resistance to water, humidity, dust, vibration, or a wide temperature range. There are also switches with IP (Ingress Protection) ratings designating protection against small solid objects, dust, low-pressure jets of directed water from any angle, and even fully waterproof, as well as military standard ratings, which add resistance to salt-water fog and extreme shock/vibration.

Conclusion

There are dozens of switch manufacturers. Some offer a broad line and specialize in a niche class of switches such as coaxial RF, ultra-tiny low-power, or higher-power AC-line switches. Nearly every vendor has useful application information at their site explaining the operation of their switches, primary applications, relevant parameters, limitations, and how to use them properly.

Although they are not considered “glamorous” or high-tech, physical, electrical switches are vital components in many product designs and require expertise in materials science and small-parts assembly to create. They are available in a mind-boggling and often bewildering range of basic types with many sub-types with choice of physical size, electrical ratings, bandwidth, contact arrangements, contact materials, and more.

The right switch can make a product stand out; the wrong one can make the product lose in the market. Switches also usually must meet different levels of industry safety or performance mandates. Next time someone says, “what’s the big deal, it’? It’s a switch” – well, they are either dealing with an almost trivial application or are naïve about the reality of these humble, passive components, which are often chosen as an afterthought late in the design cycle.

Related EE World Content

Switches: The complete guide

Miniature Toggle Switches

Dual Seal Waterproof All-in-One Toggle Switch

In defense of the toggle switch

Panel Mount Toggle Switches Feature One Through Four Pole Configurations

References

- RS Components, “The Comprehensive Guide To IP Ratings“

- Electronic Design, “11 Myths About Switch Bounce/Debounce“

- Maxim Integrated Products/Analog Devices, Application Note 287, “Switch Bounce and Other Dirty Little Secrets“