The development of powerful electric traction motors and locomotives was key to enabling visionaries to realize their dream of a mile-long tunnel under the Hudson River, linking New York to New Jersey and the rest of the mainland USA.

Over the past few years, there’s been semi-serious talk about digging new tunnels under the Hudson River between New Jersey and New York. The present pair of tunnels was been damaged by flooding from Hurricane Sandy, there’s serious wear and tear from several hundred daily passenger trains, and there’s a need major upgrade in their electrical power and signaling system, among other tasks (see References 1 and 2). Estimates are that the planning and building process will take 10 to 20 years, and 10 to 20 billion dollars.

What’s more astonishing than these estimates is that the existing tunnels are over 100 years old, and represent unappreciated marvels of civil engineering and human labor. Despite the many challenges, they were completed in under five years from conception to completion, at a cost of about $50 million (in 1900 dollars) — far less than the projected cost of the new tunnels even when you scale the dollar figures.

In a strange but sad twist, the tunnel’s terminus at the Pennsylvania Railroad station (aka Penn Station), built concurrently as an “eternal temple” to the role and dominance of railroads in general and the Pennsylvania Railroad company in particular, was torn down as obsolete after just 50 years. While the beauty and fate of the associated station (more on this below) has received the most public attention, the “invisible” tunnels are engineering and construction achievements of the highest order, especially considering the tools and machinery available at the time.

The river as a major problem

It’s hard for us to grasp the extent to which railroads dominated the US economy at the end of the 19th century and early 20th century, as the only practical mode of non-local travel for people and goods. Railroads were the drivers, beneficiaries and, in many ways, the masters of the industrial might of the country. Raw materials, finished products, food – everything traveled by rail. The Pennsylvania Railroad ran most the lines In the Northeast United States, and its president, Alexander J Cassatt, had been aggravated by one barrier to efficient operation: the connection with Manhattan island, the core of what soon formally came together as New York City. (Cassatt’s sister was the famous painter Mary Cassatt.)

In the late 1800s, New York was already the business center of the United States, teeming with immigrants, financiers, small shops, large manufacturing enterprises, and more. Yet it was “cut off” from the mainland U.S. by the mile-wide Hudson River. As a result, train travel between NY between Pennsylvania and New Jersey to the west, and Washington D.C. and the southern U.S., had to stop in New Jersey. Cargo had to be unloaded, re-loaded onto barges (some freight cars went directly onto “floats,” while passengers had to get off with their luggage, and then board ferries which left every ten minutes).

The Hudson crossing was an experience in itself as hundreds of ferries, freighters, and other vessels were on the river pursuing chaotic, semi-random paths among the many docks both sides. Traffic tie-ups and collisions were common, along with many sinkings and tragedies, especially at night or in foggy conditions.

Despite this, there did not seem to be a better alternative. A bridge seemed obvious but there were issues with access roads, ownership with other railroads, and local politics including the required bribery of local politicians (the widespread corruption was a well-established fact). Yet a tunnel also seemed technically impossible, due to the muddy silt of the riverbed which could not properly support a tunnel bored through it, or so everyone thought. Even so, that problem really didn’t matter, since everyone understood that even if a tunnel could be built, the exhaust of the coal-powered steam engines using it would asphyxiate passengers and crew, and “choke off” the locomotive’s boilers.

Electrification is key to a solution

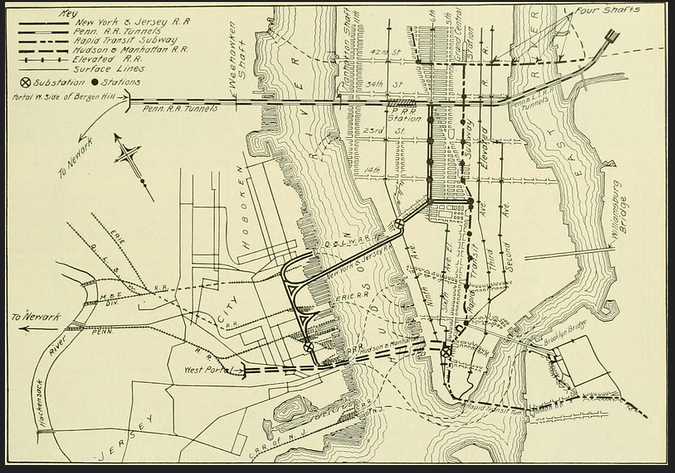

Everything changed when Cassatt, with broad and deep experience in railroad operations and a civil engineering graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, went to Europe and saw the magnificent Gare de Quia d’Orsay train station. Not only was he in awe of the station itself, but he also was awed by 45-ton electric locomotives pulling 300-ton passenger trains in tunnels along the Seine. Here was the answer to the tunnel-exhaust problem, and a vision: electric-powered trains going directly into a submarine tunnel under the Hudson River, and arriving at a train station “built for the ages” in Manhattan, (Figure 1).

Of course, vision is one thing, implementation is another. Underwater (or submarine) tunnels were difficult to build and often unsuccessful, with many started and abandoned. Cassatt hired the foremost tunnel builder in the world, Charles Jacobs, along with a leading civil-engineering manager, Samuel Rea, and they worked out a plan. He also brought on the leading architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White, known for their grandiose, classical style of architecture, to design an opulent station that would represent everything the railroads in general, and the Pennsylvania Railroad in particular, in terms of size, permanence, and stature. Cassatt also determined that the PRR would plan, manage, and execute by itself, including funding it entirely on its own with a budget of $50 million, to maintain full control.

In those days, there were no lengthy hearings, approvals, or reviews. In fact, most of the planning was done in secret so as to not tip off competitors or “spook” the Manhattan real-estate market. Cassatt sent agents door to door with bundles of cash to find and make generous offers to the owners of the 700 properties he needed for the eight-acre station and its associated powerhouse in what was a run-down, seedy area of Manhattan. In less than a year, they had spent $5 million to purchase all the needed parcels and owned a rectangle land running cross-town between 7th and 9th Avenues, and north-south between 31st and 33rd streets.

Part 2 of this article looks at the digging of the tunnels and the electric locomotives that were used.

References (these are just a few of the hundreds of references available via books and web sites)

- com, “New Hudson River rail tunnels needed so old tunnels can be repaired”

- Washington Post/Bloomberg. “Why a Rail Tunnel Under the Hudson River Is Stuck in Washington”

- Popular Mechanics, “Why Seattle’s Huge Tunnel-Boring Machine Is Still Stuck”

- Bloomberg, “Stuck in Seattle“

- Wikipedia, “Pennsylvania Railroad class DD1”

- Fandom, “Pennsylvania Railroad Class DD1”

- CityLab, “10 Gorgeous, Nostalgic Photos of New York’s Old Penn Station”

- Mashable, “1910-1963: The destruction of Penn Station”

- EE World, “The first undersea transatlantic cable: An audacious project that (eventually) succeeded, Part 1

- EE World, “The first undersea transatlantic cable: An audacious project that (eventually) succeeded, Part 2”

- Wikipedia, “James A. Farley Building”

- American Experience PBS Video, “The Rise and Fall of Penn Station,” 2014

- New York Preservation Archive Project, “Pennsylvania Station”

- Jill Jones, “Conquering Gotham—A Gilded Age Epic: The Construction of Penn Station and Its Tunnels,” Viking, 2007

- Lorraine Diehl, “The Late, Great Pennsylvania Station,” Four Walls Eight Windows, 1996

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.